Rust is the nemesis of every classic car enthusiast. That dream vintage vehicle, seemingly pristine, can often hide insidious corrosion lurking beneath the surface. Even cars that appear to have escaped the tin worm’s grasp may reveal hidden damage once stripped back to bare metal. My first classic car restoration, a supposedly rust-free Californian import, taught me this lesson firsthand. Beneath layers of paint and filler, I discovered a history of poorly repaired dents and, of course, rust in the usual suspects like under the trunk lid and kick panels. One front fender was a patchwork of brazing and filler, subtly misshapen compared to its counterpart.

This experience highlighted a crucial reality for classic car restorers: unless you’re working on a wildly popular model with readily available replacement panels, mastering rust repair, including fabricating and installing patch panels, is essential. While sourcing original, undamaged panels is ideal, often repair is the only viable path, especially for less common classics. Even if you’re simply aiming to refurbish rather than fully restore, ignoring rust is a recipe for future headaches. And for a full restoration, stripping back to bare metal is non-negotiable to address existing rust and old, often poorly executed, repairs. Cars over two decades old, even meticulously maintained ones, are likely harboring hidden rust issues.

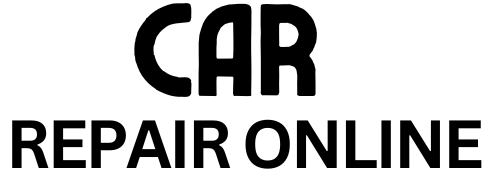

Close-up view of rust damage on the lower hinge panel of a classic car door, highlighting the typical corrosion areas in older vehicles.

Whether dealing with common rust spots or more extensive damage like rusted-through rear fenders or floor pans, cutting out the rot and replacing it with healthy metal is the only permanent solution. Rust inhibitors and converters can temporarily halt surface rust, but they don’t address the underlying structural weakening caused by deep corrosion. Oxygen will inevitably reignite the rusting process. Fortunately, repairing rust holes, while demanding patience and skill, is a manageable DIY project.

Choosing Your Welding Method

Over the years, various methods have been employed for attaching patch panels, from brazing and pop riveting to welding. Brazing lacks the structural strength of welding, and pop rivets create lap joints prone to further corrosion within the overlapped metal. Butt welding stands out as the superior technique. Historically, torch welding (oxy-acetylene) was the standard, demanding considerable skill and practice to avoid warping and melting the sheet metal.

The advent of MIG (Metal Inert Gas) welders revolutionized auto body repair. While MIG welds may not be as aesthetically refined as torch welds initially, they are equally strong, significantly easier to learn, and ultimately ground smooth anyway. MIG welders are now commonplace in professional body shops and accessible to home restorers.

For DIY enthusiasts, light-duty MIG welders operating on standard 110-volt household current are readily available at reasonable prices (around $500 for models like the Lincoln MIG PAK 10, mentioned in the original article, though newer models exist now). These are perfectly adequate for classic car rust repair. Many manufacturers offer beginner-friendly resources, including video tutorials, to quickly get you started. With some practice on scrap metal to master wire feed and nozzle angle, you’ll be ready to tackle your car.

Selection of fabricated patch panels prepared for rust repair on a classic pickup truck, illustrating the variety of shapes and sizes needed for different body sections.

Safety First: Welding necessitates crucial safety precautions. Electric welding emits intense glare that can severely damage eyesight. Always wear a welding helmet with the correct shade level. Molten metal splatter is another hazard, so leather welding gloves and protective clothing are essential. Sunglasses offer no protection during welding. A welding cap is advisable to protect your hair. Keep a fire extinguisher and first-aid kit readily accessible in your work area.

If sourcing patch metal from a donor car, meticulous cleaning is paramount. Remove all paint, dirt, and grease before welding. Heavy-duty aircraft paint stripper or hot water and crystal drain cleaner (for smaller panels, in a metal bucket – use with extreme caution, always wear goggles and neoprene gloves, and keep away from children and pets) can be used for stripping. Thoroughly rinse with clean water, dry, and remove surface rust with a wire wheel or sandpaper, followed by a metal prep product like Pre-Kleno or Kwik Prep before welding.

Image of a compact 110-volt MIG welder setup, demonstrating the accessibility of modern welding equipment for home-based car restoration projects.

Preparing Patch Panels and Metal

Matching the gauge (thickness) and carbon content of the patch panel metal to your car’s original body steel is vital. While sophisticated carbon content analysis exists, a practical field test involves using a surface grinder on both metals. If the spark patterns are similar in color and type, the carbon content is likely compatible. Experiment with scrap metal to familiarize yourself with spark variations from different metals.

Using mismatched metals can lead to welding difficulties, with one metal melting before the other reaches welding temperature. Furthermore, differing metal properties can create challenges when shaping and finishing the repaired panel. Common donor sources for patch panels include hoods and roofs from other vehicles, as they often provide large, flat panels of suitable gauge and carbon content, and are frequently rust-free. New sheet steel can also be purchased from metal suppliers. For my ’58 Chevy Apache pickup project, an early 80s Audi hood proved to be an ideal source of patch metal.

Butt Welding vs. Lap Welding: For exterior body panels, always prioritize butt welding patch panels. Lap welds, while simpler to execute, are prone to rust within the overlap and can create stiffness, hindering the panel’s natural flex. Lap joints can also become visible as the repair ages and require more filler for a smooth finish. However, lap welds are acceptable for non-visible areas like floors, inner panels, and trunk floors where they can be protected with undercoating.

Creating Templates for Precision Patches

Cardboard, such as shirt cardboard or cardboard box material, is excellent for creating patch panel templates. An X-acto knife and a wood block are sufficient for cutting. A flexible cloth tape measure is ideal for taking accurate dimensions. If you encounter difficulties visualizing complex shapes, seek assistance from someone with sewing pattern experience, as the principles of pattern making for clothing and car bodies are analogous.

Close-up of welding practice, emphasizing the importance of achieving a consistent weld bead with proper penetration without overheating and damaging the metal.

Creating the template before cutting the rusted metal is often the easiest approach. Use the template to mark and cut out the corroded section. To accommodate curves in your template, lightly score (do not cut through) the back of the cardboard at intervals to allow for bending. Tape the template in place on the car body and carefully assess its fit before cutting any metal.

Once satisfied with the template, transfer it to your chosen patch metal, leaving about ¼-inch of extra material around the template outline. If using a car hood, cut a manageable section first. Cut out the patch panel using aviation tin snips, which provide a cleaner edge than standard snips.

Heavy-duty aviation tin snips, showcasing the tool used for precisely cutting patch panels from sheet metal, essential for clean and accurate rust repair.

For sharp 90-degree bends, use soft wood blocks (like 2×4 scraps) in a vise to clamp the metal. Use a third wood block to gently bend the metal over the clamped blocks. Heat from an oxy-acetylene or propane torch can facilitate shaping.

For gentle curves, shape a piece of wood to the desired radius using a bandsaw or file. Use this shaped wood as a form and tap the patch panel over it with rubber or plastic mallets, or body hammers and dollies. A shot bag (leather pillow filled with lead shot or a canvas bag filled with sand) provides a flexible base for shaping metal panels.

Cardboard templates for patch panels, illustrating the process of creating accurate patterns before cutting replacement metal for rust repair.

Cutting Out Rust and Welding in Patches

A saber saw is ideal for cutting out rusted panels, but a die grinder with a cutting wheel or heavy-duty aviation tin snips (both right- and left-bladed) are also effective. Avoid oxy-acetylene cutting torches as they create ragged edges and warp the metal due to excessive heat.

Patch panel temporarily tacked into place on a classic car body, demonstrating the initial stage of alignment and securing the patch before final welding.

Cut the patch panel slightly oversized to allow for trimming and precise fitting to the cleaned-up opening on the car body. This step requires patience and meticulousness. Ensure body lines and moldings align perfectly. Misaligned panels are immediately noticeable and detract from the quality of the repair.

Securely hold the patch panel in place for welding using C-clamps or specialized auto body vise grips. Begin by tack welding at the ends of longer cuts and strategically around the panel perimeter to hold it firmly. Step back and double-check alignment. Correct any misalignments now by grinding off tack welds and adjusting the panel.

Diagram illustrating the recommended welding sequence for patch panel installation, emphasizing tack welding, spacing, and controlled welding to minimize heat distortion.

Next, tack weld in the middle sections of the cuts, alternating around the patch panel to distribute heat and minimize warping. Continue tack welding, spacing the welds about ½ inch apart. Use a hammer and dolly to gently correct any minor warping in the patch panel or surrounding fender. Finally, weld the patch panel in place, welding in short, ½-inch sections, alternating across the seam to prevent overheating and warping. Use a general-purpose dolly and hammer to flatten each weld section while it’s still warm, reducing the amount of finishing work needed later.

Allow the welded area to cool completely. Smooth the welds with a coarse vixen file or grinder. Use a hammer and dolly to address any remaining warping or low spots. Cosmetically finish the panel using plastic filler or traditional lead body solder. A body spoon is useful for flattening larger warped areas. Metal shrinking techniques can be employed for final shaping refinements. Apply a waterproof enamel primer to the repaired panel immediately after metalwork is complete to prevent flash rust while you continue with other aspects of the restoration.

For achieving an authentic factory look on lap-welded joints (e.g., floors, inner panels), replicate spot welds by drilling small holes (around ⅛ inch) in the overlapping panel where original spot welds would have been. MIG weld through these holes to join the panels, creating a convincing spot weld appearance.

With patience, practice, and readily available tools, you can effectively repair rust holes and restore the structural integrity and beauty of your classic car’s body. Mastering patch panel fabrication and welding opens up a world of possibilities for even severely damaged classics. Don’t be intimidated – start with practice pieces and gradually work your way up to tackling rust repair on your prized classic.